FTP for TV Stations Available Here

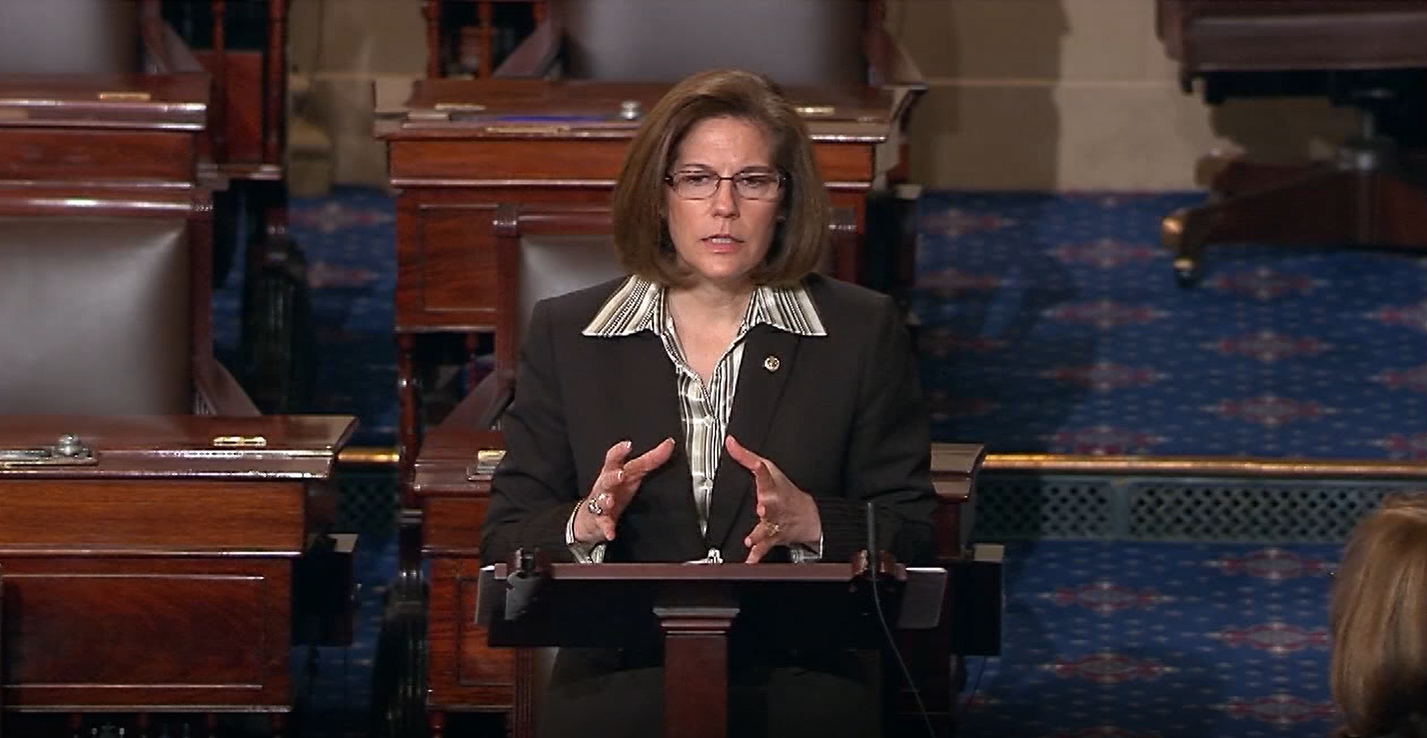

Washington, D.C. – U.S. Senator Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.) delivered a speech on the Senate floor, urging her colleagues to support an amendment she introduced that would preserve important protections against housing discrimination. A video of the speech is available here.

Below are her remarks as prepared for delivery:

I ask that the quorum be dispensed with.

I recently read an article from the Center for Investigative Journalism about a young woman named Rachelle.

At the time, Rachelle was in her early thirties and living in Philadelphia.

She was making $60,000 a year as a contractor at Rutgers University.

She had savings, good credit, and an undergraduate degree from Northwestern.

When she first went to apply for a home loan, she thought she would be the perfect applicant.

On paper, it seemed that way. But a few weeks later, she received an email informing her that her application had been denied.

In the email her broker told her that, because she was a contractor and not a full time employee, her application was too risky for the bank to approve.

She was at a loss. She had been planning to purchase a home for years, and thought she had done everything right.

She then asked her partner, Hanako, to sign onto the application with her.

At the time, Hanako was working a few hours a week at the grocery store, making $300 a month—about $3,600 a year.

Hanako tried calling the bank to speak to a loan officer about the application. To Rachelle’s surprise, the loan officer picked up.

He was attentive, helpful—even friendly to Hanako.

A few weeks later, he approved the couple’s loan.

Now, this makes no sense.

Rachelle was the one making an income in the upper five figures.

Rachelle was the one with good credit.

Rachelle was the one paying for Hanako’s health insurance.

But Rachelle is black. And Hanako is biracial: Japanese and white.

This story did not take place in 1930, when it was legal for housing lenders to discriminate on the basis of race.

It did not take place in 1968—the year banks were formally banned from using race as a factor in deciding home loan applications.

It took place less than two years ago, in 2016.

Today, fifty years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, stories like Rachelle’s are all too common.

For any person of color who has tried to navigate the housing market, Rachelle’s experience is a case of déjà vu.

We know now that Rachelle was a victim of “redlining.”

“Redlining” is a term that describes the practice of denying goods or services to people on the basis of the color of their skin.

The term originated in the 1930s, when redlining was the official policy of the Federal Housing Administration.

Back then, federal officials divvied up cities and assigned a color to each neighborhood. The color system was supposed to help mortgage lenders know where to invest.

Green and blue neighborhoods were home to desirable borrowers with good credit.

Yellow or red meant: “risky borrowers live here. Don’t invest!”

The practice became known as “redlining” because the FHA would draw red lines on city maps to designate quote-unquote “bad” neighborhoods.

For the FHA, a bad neighborhood was defined by the color of your skin.

Redlining was banned in the 1960s, but as we learned from stories like Rachelle’s, the practice still goes on under the radar.

So much so that in 1975, Congress passed the Housing Mortgage Disclosure Act to help regulators identify when it was going on.

But even with the new requirements, redlining continued. And, in the 1990s, the financial industry began selling a thing called the subprime loan.

Subprime loans have high fees, adjustable interest rates, and payment shocks—characteristics that made them extremely dangerous.

People who weren’t approved for traditional loans were offered subprime loans instead.

In 2008, when the markets crashed, subprime loan holders saw their interest rates skyrocket.

They suddenly became unable to afford to stay in their homes.

And who do you think was most likely to hold one of these so-called subprime mortgages?

People living in redlined neighborhoods.

People of color.

People who had been denied access to traditional loans.

My home state of Nevada was one of the hardest hit states in the country by the financial crisis.

We had the highest foreclosure rate for sixty-two straight months. We had the most number of underwater mortgages, and over 219,000 families lost their homes.

Anyone driving through parts of Las Vegas and Reno in 2009 could see boarded up houses, “For Sale” signs, and empty lots everywhere.

On many streets, you would see more houses in foreclosure than not.

And while all neighborhoods suffered, African American, Latino, and Asian and Pacific Islander communities were hit the hardest.

Entire neighborhoods were hollowed out.

Trillions of dollars were lost.

I was Attorney General of Nevada at the time. We did everything we could to fight for homeowners and help them stay in their homes.

As this was going on, I asked myself, “How could this happen?”

The federal government was supposed to regulate these banks. Where were they? Why didn’t they put a stop to these practices before it all came crashing down?

The federal government was supposed to be the watchdog, but they were letting banks write their own rules.

As Attorney General of Nevada, I sued the big banks for their fraudulent practices, and secured $1.9 billion to help Nevada homeowners.

Then, in 2010, federal lawmakers passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act to ensure that what we saw in 2008 would never happen again.

This bill was not perfect, but it did a lot of things right.

It strengthened oversight of the big banks.

It made the big banks undergo stress tests and develop bankruptcy plans.

It also strengthened HMDA reporting requirements to help regulators fight back against discriminatory, racist redlining practices.

Banks say they don’t treat borrowers differently but the data shows a different story.

Redlining remains a major problem for communities of color.

The legislation we’re now considering—S. 2155—would roll back Wall Street Reform.

It includes a section—Section 104—that would repeal many of the reporting requirements we added after the financial crisis.

Some rural and low-income communities are predominately served by small lenders.

If this specific loan data is removed for them, government officials, researchers and the public will not have information on the quality of loans made. Nor will they know about the credit scores of the borrowers. Or even a way to easily track the loans after they are sold to an investor.

When I was Attorney General, I needed information on the quality of loans in the state to protect consumers. Where were the teaser rate resets made? Who were the homeowners who might not be ready to pay 20% more on their monthly mortgage?

With everything we saw ten years ago, I cannot now believe that we’re considering restricting access to this kind of data.

I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have strong enough protections against housing discrimination.

This is why I have introduced an amendment to strike Section 104, to preserve access to data we need.

With better information, we could have prevented a crisis in which 12 million people lost their jobs. In which the banks took the homes of more than seven million people.

Let’s not take away access to this information. Let’s not make the same mistakes we made ten years ago.

And so I urge my colleagues—join me. Vote for fairness. Vote for equality. Vote for inclusion.

Vote for everyone who got burned by the big banks.

Vote for folks like Rachelle, who just need a break. Who just need a fair mortgage so that they can buy their first home.

Support my amendment to prevent loan and housing discrimination. To protect access to this data. To protect the progress we made under Wall Street Reform.

Thank you M. President, I yield the floor.